There are two kinds of value in business. One kind you can touch: plants, equipment, inventory, real estate, headcount; the tangible assets. You can find all these on a balance sheet. They can be counted, appraised, and depreciated.

The second kind is something far less tangible but far more powerful: your brand and the intangible equity it holds. Band is your moat, your path to sustainable success. It creates pricing power and opens margins. It drives future cash flows and is a leading driver of value creation and long-term success.

First, a little structure. Brand equity represents the commercial value derived from consumer perception of a brand name and experience rather than from the product or service itself. It’s the reason consumers pay 30% more for an iPhone or for fancy water in a can with a skull on it. It’s why two chemically similar fragrances command wildly different prices based solely on whose name appears on the bottle. Brand equity, being intangible and grounded in psychology, is, and always will be, notoriously difficult to quantify or measure. This challenge makes measuring brand intangibles a critical capability for modern businesses.

Brand equity grows over time through multiple interconnected intangibles, including brand awareness, brand associations, brand values and purpose, perceived quality, brand loyalty, and brand interactions. All of these play a critical role in shaping consumer perception and the relationships we build with a brand.

Consumers today, both B2B and B2C, buy more than features and benefits. They buy emotions such as trust, confidence, and image. They find affinity with a brand’s equity; its identity, status, heritage, values, and meaning. They purchase the right to associate with everything the brand represents and the benefits that come with it. It’s why brand equity is so extraordinarily valuable. It delivers financial benefits that defy traditional economic logic. A company’s brand creates a moat around its market position that competitors cannot easily breach and generates consumer preference that sometimes transcends rational evaluation.

A case in point: the value of brand equity.

This is a classic. In 1998, Rolls-Royce enjoyed the most powerful brand equity in the automotive world. It was the category’s crown jewel. For ninety-four years, the name built unassailable brand capital around British heritage and craftsmanship, ultimate wealth and success, refined taste, and timeless elegance. The Spirit of Ecstasy hood ornament had become a universal symbol for the height of success. The brand name appeared in song lyrics, films, and literature as shorthand for prestige. Unaided brand awareness of the meaning of Rolls-Royce was universal. This accumulated brand equity was intangible. You couldn’t audit it, weigh it, warehouse it, or put it on a P&L, but its effect on consumer behavior and willingness to pay was undeniable. And that equity had tangible financial benefit.

As Volkswagen would learn, Rolls-Royce’s equity was far more valuable than all its tangible assets combined.

Here’s how it played out.

In 1998, Rolls-Royce Motor Cars was up for sale. It became the focus of a bidding war between Volkswagen Group and BMW Group. BMW was first in with a bid. But VW’s CEO, Fendinant Piëch, coveted the Rolls brand and upped BMW’s offer by around 30%, to the tune of $559M. That was big money, and Rolls jumped on it. The Volkswagen Group purchased Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, Ltd., the operating company. It acquired the manufacturing business and related operational and tangible assets. And so that is what they got, and VW celebrated. But actually VW lost. They had acquired only the hard asset of Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Ltd., including:

- The Crewe manufacturing facility.

- Production equipment and tooling.

- Design and engineering operations.

- Supplier and dealer relationships.

- The skilled workforce.

- Manufacturing and operational know-how.

But VW did not get the good stuff. BMW Group may not have won the bid for the operating company, but they ended up with what really mattered. You see, the Rolls-Royce name was owned by Rolls-Royce PLC, the aircraft engine maker, not Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Ltd. And BMW and Rolls-Royce PLC had a cozy relationship. Being a brand-savvy company, BMW inherently understood the value of the trademarks and intangible assets VW inexplicably overlooked. While VW was drinking champagne, Rolls-Royce PLC sold the ownership rights to the name and brand mark to BMW for only $52M.

The Volkswagen Group acquired a factory to make the cars, but not the brand to sell them, and BMW, for a fraction of the cost, acquired the most prestigious brand in the world.

The story goes that because BMW made the engine for the Rolls at the Crewe factory, they had some leverage. They threatened to stop sending engines, effectively crippling VW’s production capability. Volkswagen had to cut a deal. They would keep the factory and the Bentley brand, and BMW would grant them temporary licensing rights to use the Rolls-Royce brand name until the end of 2002. Then BMW would take the Rolls-Royce brand and build Rolls-Royces in its own factory. In 2003, the two brands ended their relationship, and BMW assumed full operational and brand control.

Volkswagen acquired tangible industrial assets for $559M, failing to ensure they were the most valuable long-term assets. They didn’t understand, or ignored, the critical importance of the brand. Or conceivably, (or inconceivably) their legal team and board simply did not complete thorough due diligence. If they had, they would have discovered that the brand and the factory were legally and economically separate, and would have restructured the deal. Not getting the brand was a major gaffe. And an expensive one.

As all students of brand know, long-term value creation would follow the brand and its equity, not the hard assets. Volkswagen didn’t get the brand identity they thought they’d acquired. BMW acquired the intangible brand assets, the real financial jewel. You gotta hand it to BMW.

VW bought a factory. BMW bought equity. Factories die. Equity can live forever.

The Staying Power of Brand Intangibles

Volkswagen had purchased the wrapping, not the gift. They owned the means of production but not the meaning. They could build cars, but they could not legally grace those cars with the brand that justified their pricing power in the first place.

BMW didn’t approach the opportunity as a factory optimization problem. BMW saw the situation for what it actually was: a brand strategy opportunity. They saw the separation between tangible and intangible assets and VW’s mistake as a huge opportunity to acquire the Rolls-Royce trademark rights.

They got the logo and the accumulated associations, perceptions, and meaning built over 94 years. It was all intangible, nothing you could touch. And it would prove to be worth vastly more.

Between 1998 and 2003, BMW owned the Rolls-Royce trademark but had no cars rolling out of its own factory. For five years, the Rolls-Royce brand existed in an in-between state, owned by BMW, but manufactured by Volkswagen. If building brand equity were merely a marketing tactic, this should have weakened it.

It didn’t.

The brand remained strong through the transition. Customers kept buying. Anticipation built for BMW’s interpretation grew. The strength of the brand’s heritage, prestige, and uncompromising quality actually grew independently of ownership. That kind of brand resilience is one of the most underappreciated financial characteristics of strong brand equity.

Strong brands are durable.

A strong brand can survive shocks that would destroy product-led businesses. It buffers mistakes. It sustains desire. It buys time. And time, in business, is expensive.

BMW bought a gold mine. It wasn’t starting from zero. They didn’t have to build a new luxury car brand. They were inheriting nearly a century of equity that was so powerful it became cultural capital. It would have cost BMW hundreds of millions and many years to build that kind of equity.

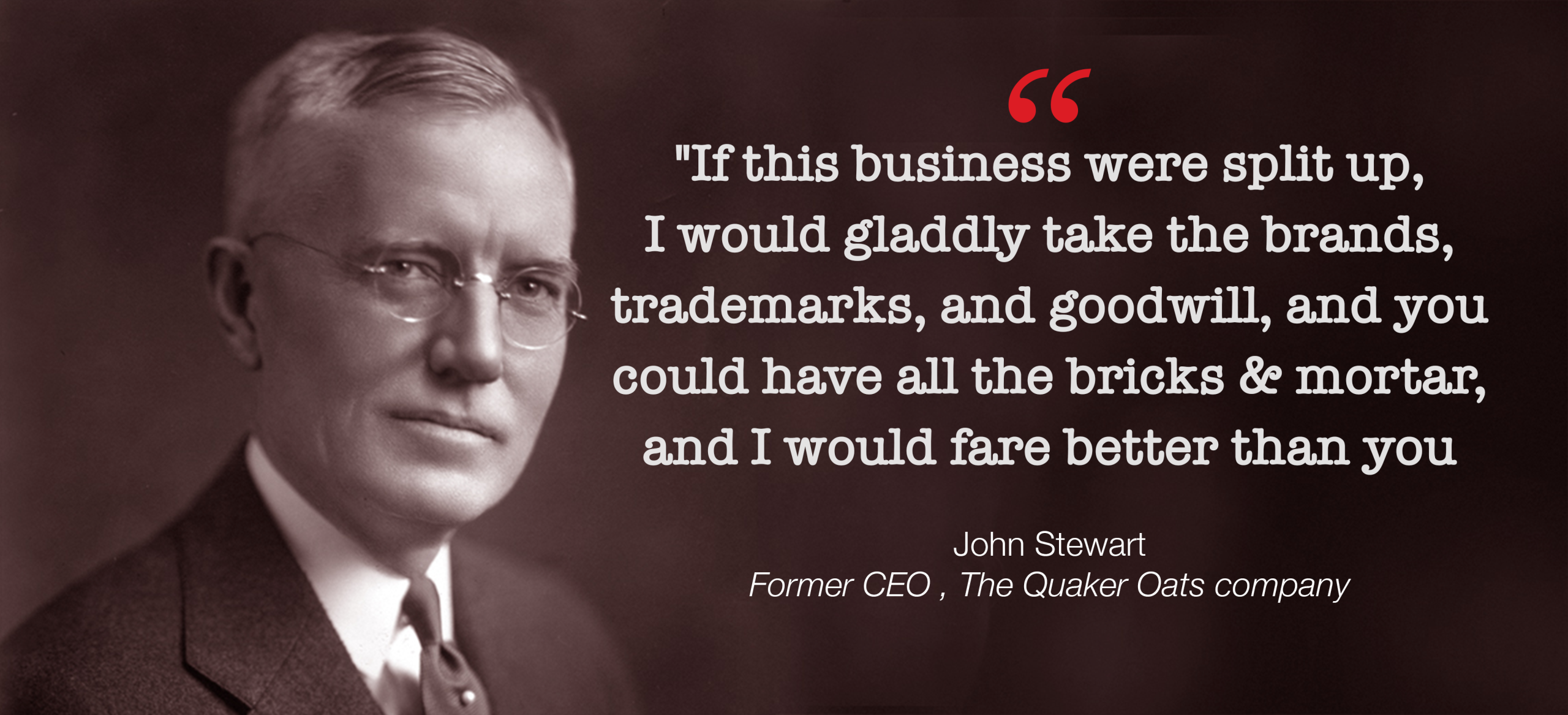

This is the advantage of brand equity. It becomes stubbornly persistent. Its benefits compound. This is not a new idea, smart leaders have always known this.

BMW has always been a brand-driven company. In their infinite wisdom, they decided not to manufacture Rolls-Royce inside BMW plants. Sure, that would have been more efficient. They could have shared tooling, infrastructure, and supply chains. If you are an accountant, it’s classic scale economics and would seem to make perfect sense.

But as a brand-centric organization, they understand how to leverage the brand capital they acquired. They knew that if consumers perceived Rolls-Royce as an expensive BMW under a different mark, they would lose the brand equity they had acquired. And so BMW built a dedicated facility at Goodwood, UK. It was all Rolls-Royce. It might seem like an expensive decision, but in fact, it was a brilliant decision made by really smart brand strategists.

Operationally separating BMW and Rolls-Royce was not a short-term economic decision. Obviously, there would be considerable capital expenditure required to build a new factory. It was a brand decision. They were preserving all the capital of 94 years of brand equity. They were playing the long game.

In 2003, BMW launched the Phantom, the first Rolls-Royce built under BMW ownership. The brand strategy was clear: honor the Rolls tradition and heritage. The Phantom was unmistakably Rolls-Royce, and the brand maintained what it always had been: a globally recognized badge of wealth and status.

- BMW preserved the Rolls DNA, physically and spiritually.

- It preserved Roll’s British identity and its heritage.

- It allowed BMW to maintain its core positioning, as dilution can work both ways.

- The Rolls plant itself became a brand experience destination.

- It insulated the organizational cultures so Rolls-Royce craftspeople were not BMW employees who build fancy cars.

The Final Chapter – The Economics.

BMW reportedly invested about $107M building the Goodwood plant and developing the first new Rolls-Royce under their ownership. Add the $52M brand and trademark purchase for a total of roughly $174M. A pretty sweet deal made by brand strategists, not accountants.

Some might question the exact amounts, but the illustrative point remains. A Rolls-Royce Phantom costs roughly $515K today, while manufacturing costs are estimated at $275K. That’s brand equity converted into pricing power, margin, and revenue. BMW is realizing about a 120% premium pricing attributable to Rolls-Royce’s brand equity.

Not too bad.

Rolls-Royce did about $1.2B in revenue in 2024 at a pre-tax profit of about $165M. It delivered 5712 vehicles in 2024, the third-highest year on record. Its cars appreciate an estimated 10% year-on-year. While I was unable to find a confirmed value for the Rolls-Royce brand today, many believe it’s worth well over $1.0B, and some consider it much higher. Today, Brand Finance ranks Rolls-Royce as one of the top ten automotive brands in the world.

In the end, Volkswagen paid $559M for… physical stuff.

BMW paid $52M for the meaning of the Rolls-Royce brand.

And they were smart enough to understand the value of what they acquired and how to amplify that brand capital.

This difference in philosophy is the real takeaway here. Being brand-centric is an operating philosophy, a best practice. I don’t care what category you are in, what size your business is, B2B, B2C, or B2B2C. Building brand capital and gaining the resulting equity is central to value creation and long-term financial success.

It’s how every company should think about how it builds its business. It requires vision, an understanding of the power of things you can’t measure, and the knowledge that you are playing a long game that offers significant financial rewards.

Intangibles build brand equity. And equity builds enterprise value.

After all, every company is a brand. The question is, what are you doing with yours?

Looking to build your brand equity? Hit the contact form and let’s chat.